Over the NZ summer, I deliberately made time to nourish my professional self.

Inspiration came from 5 podcasts, 2 books and a 2 short but atmospheric films.

I’d squirrelled dozens of potentially inspiring articles, podcasts and videos over the year, waiting to filter them for quality, then absorb them… undistracted, to the sound of cicadas.

A few were memorable, including:

- A peculiar ‘outsider view’ on UX research,

- Podcasts on social research and why people do what they do,

- Interviews with designers I admire about their work, and approaches to product development,

- A couple of rather chilling ethno-books by people who gave their all to understand another people.

- A couple of gorgeous videos spotlighting the beauty of heavy manufacturing – sheffield style,

- A short surf adventure in Iceland, captured in inimitable ironic Kiwi narrative.

- … and some envy-inducing lifestyle portraits of people who’ve made creativity into a lifestyle,

Here’s a snapshot of each, and why I found it worthy brain fodder for my work in design / research:

5 Podcasts

UX seduction at Etsy

Journalism meets UX research. This account of the interviewee’s perspective in a ‘usability test’ is a surreal experience given I’ve conducted hundreds of these sessions in my time.

The host of the podcast feels more like they’ve been part of an experiment than ‘helping improve a product’, and (tries to) delve into the ethics behind the way e-commerce sites steer our minds.

Hearing this makes me want to interview the interviewees from user research sessions to find out what level of cynicism and undercurrents of curiosity really does ship as standard with participants in these studies.

‘The big interview’ with Thomas Heatherwick & Monocle

I used to ride past his office in London when the models for his ‘rolling bridge’ were in the window, but the bridge hadn’t become a reality.

Now it’s in his back catalogue, and Terence Conran has declared Thomas Heatherwick ‘the Leonardo Da Vinci of our time. … a handle he’s clearly not comfortable with.

Though he gets a bit earnest at times, I was taken by his lack of ego. A humble designer untethered to a medium with a solid worship of idea over process.

He reminds me at times of the profile of Marc Newson, who in ‘Urban Spaceman’ share the same comments about being material and subject matter agnostic as a designer.

Thinking allowed

Fascinating sociology podcasts from the BBC. Laurie, the curious interviewer frames up myriad topics beautifully, then chats with people who’ve studied people in that context.

It’s good stuff. Highly conversational, so you don’t need to wade through the academic fluff as you find out about things like what motivates middle class kids who want for nothing but become drug dealers, or changing attitudes to how we navigate our careers, to children’s changing attitude to money.

Perfect podcasts for a walk around the block. If your block takes about 20 mins.

Paul Adams on Product

Never short on an opinion, and always worth listening to, Paul Adams is quite the influential voice on what it takes to make a great digital product.

We worked together at Flow, a company since absorbed into Europe’s largest UX consulting agency. Now – after serving a Silicon Valley sentence – He’s putting his learnings into play at Intercom, in Dublin, where he’s using what he refers to as the ’6-6-6’ roadmap for product development.

For those who (like me) suffer fatigue from the newfangled recipes for success, it’s summed up here as a 2min read, but the podcast is worth a listen to any product strategy or team leader.

Guerilla interviews in South Auckland

This is guerrilla street interviewing at it’s best, by a master who really connects.

John Campbell’s authentic and probing dialogue makes you feel like you’re there with him. This is all laid down with brilliantly executed post production to stitch the story together.

There’s only a couple of these articles, but they are worth a listen, as he interviews people at the low end of the socio-economic spectrum, and very quickly gets down to brass tacks about their day to day struggle to live in our biggest city.

2 books:

On the run, with Alice Goffman

Reading this book is a little like a personal account of living in the series ‘the wire’…

…but instead of an HBO production crew, it’s seen through the lens of an ethnographer.

New York book review calls it an ‘ethnographic classic’, but it’s also been controversial.

Alice, a middle class academic moved in and spent six years living in a troubled Philadelphia neighborhood and saw first-hand how teenagers of African-American and Latino backgrounds are “funneled down the path to prison”.

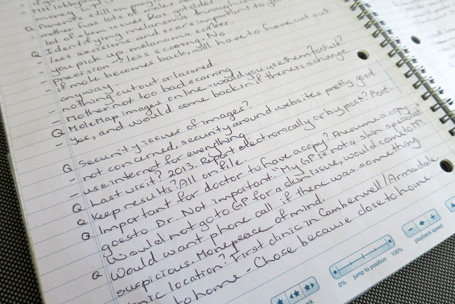

This is journalism meets ethnography, and you’d expect rigour from the daughter of the “most important sociologist of the last 50 years” … So reading about her in-the field practices of note taking, logging of events etc. .. I shudder to imagine how much data she was wading through while examining these lives at such close range.

Academic sociologists felt she was too close to her subjects and took liberties in the way she wrote, while Journalists, (likely stunned at the depth and richness of her account) simply picked holes in the details, dismissing it’s value as a true account.

If you haven’t got the time to read the book… here’s a TED

Patched. when ethnography goes underground.

This book is the result of New Zealand’s largest ever study of gangs in NZ, with much of the story captured via a long and dangerous ethnography.

“I hung out with the gangs” says Jarrod Gilbert, and the stories he’s dredged up paint a rich and sometimes raw picture of this part of our social history.

He spent six years researching gangs, which meant drinking with them, listening to them, tuning motorbikes together and figuring out what to say and what not to say. He admits he was “on the wrong end of a couple of beatings” and his liver took a beating as well.

This all led to a prize-winning academic book, Patched, but like Alice and her book on life as a fugitive in Philadelphia, This author too has had their work controversially discredited by authority (in this case the Police) because he was too close to the subjects.

2 Short films

For some eye candy I soaked up these two gems:

Barry Can’t arf Weld.

A totally gorgeous piece of atmosphilm – this short but powerful video essay rips into you with sound and motion.

Follow the journey of a few kilos of molten metal all the way to becoming a railway bogey. It’s so raw, noisy and dirty it makes you want to reach for the Swarfega.

…But then you kinda wish you could don a pair of steel caps and join in the fun in the dark and forbidding bowels of this Sheffield foundry.

Delicious.

‘Brass monkey’ surfing in Iceland.

A somehow timeless surfing ‘roadie’ flick. Filmed in in Iceland of all places by three Kiwi wax-heads mad enough to take this on.

Equal parts warming and super frosty, with the kind of dry, tongue-in-cheek-narration to bring you along on the romance of the trip.

Oh, did I say 9?

… come on, just one more …

As a some-time architect of my own lifestyle. I’m a hoover for inspiration … pondering other people’s existence. … and here at Freunden von Freunden (friends of friends) is where I found a stack:

These are styled portraits showcasing the lives of a privileged few creative people who have made a life from what they love and seek and create. Including a few Kiwis

Ok, and one more makes 11

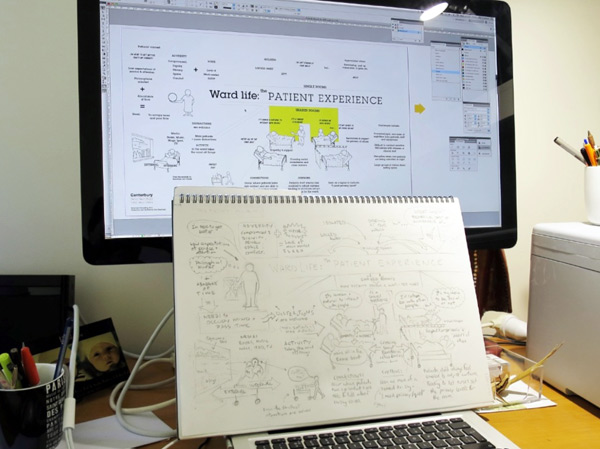

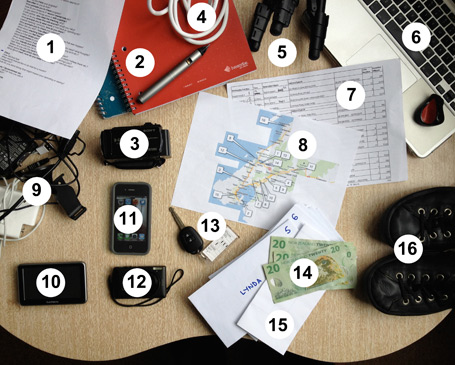

I’ve also been piecing together a wee story about my own product development – of Mr. Tappy, a mobile UX research tool. I’m as proud as I am surprised with how it’s evolved.

Great to have found the time to indulge, and now share some brain fodder and use some of those muscles which -during the year- only get a 2 minute workout on short articles.

Thanks for reading and here’s to 2016!

Google have a stab at answering this question in their article ‘

Google have a stab at answering this question in their article ‘

A couple of universal truths stand in the way of discovering what people actually think and do:

A couple of universal truths stand in the way of discovering what people actually think and do: